Dorothée Pullinger—this name doesn't appear in many publications, and in Polish, there's not even a Wikipedia entry. It seems we're the first in Poland to present this exceptional figure, though her extraordinary story is a ready-made script for a film. She was a pioneer in an industry where women didn't have a voice at the time. She designed a car perfectly suited to women's needs, proving that women are not only users but also creators of the automotive industry. She ran a women's car factory, paving the way for future generations of female engineers in a world that until then had belonged exclusively to men.

Dorothée Pullinger knew what she wanted to do even as a teenager. In 1910, after many hardships, she began working as a draftsman at the Arrol-Johnston factory – Scotland's oldest and largest automotive company, which her father managed. She wanted to follow in his footsteps as an engineer and car designer – a sentiment that at the time evoked condescending smiles. When, in 1914, full of ambition, she applied to the Institution of Automobile Engineers, she was met with the absurd answer: "The word 'person' means male, not female." But this wasn't the end; it was the beginning.

World War I, though tragic, proved to be an opportunity for her. Dorothée took over the management of a shell factory, employing and training 7,000 women, many of them refugees from France and Belgium. For her work, at the age of just 26, she was awarded the Order of the British Empire, and her contribution was duly recognized. She returned to the Society of Engineers, this time as the first woman in its history.

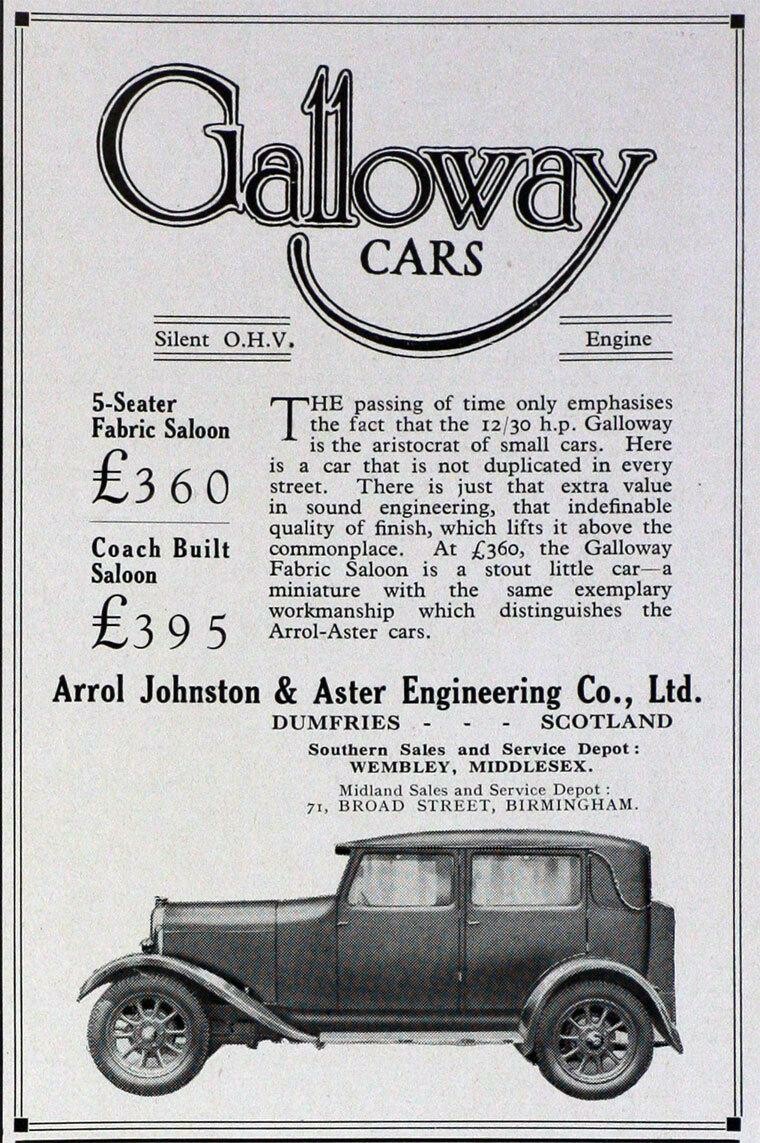

The real revolution, however, came when Dorothée took over as director of Galloway Motors. She decided to leverage her experience and create something unique: a car perfectly suited to women's needs. She broke away from the masculine standards that dictated that cars should be large and unwieldy, with the gear shift on the outside. Her design – the Galloway – was a masterpiece of ergonomics and feminine intuition. It was lighter and smaller, with gears located inside the cabin rather than outside, a real godsend for women wearing long dresses and skirts. The seats were raised for better visibility, and the steering wheel was reduced to make it more comfortable to operate. Furthermore, it was one of the first cars to feature a rearview mirror as standard equipment.

The company she headed was unique. It employed mostly women, and the engineering apprenticeship programs were shorter because, she believed, women learned faster. Moreover, to make their work more enjoyable, she set up two tennis courts on the factory roof. It was a company "by women, for women," in the truest sense of the word.

Dorothée wasn't just an engineer: she was a passionate motoring enthusiast. In 1924, driving her Galloway, she won the Scottish Six Day Car Trials, proving that her car was not only practical but also durable. Although Galloway production ended in 1929, Dorothée didn't slow down. With her husband, she founded a chain of laundries, and during World War II, she was the only woman to serve on the Industrial Panel of the Ministry of Production. In her old age, she moved to Guernsey and, as local writer George Torode recalled, enjoyed driving her Galloway around the island, flouting the road rules. She died in 1986 at the age of 92. She dedicated her life to demonstrating that women could be not only passengers but also engineers, managers, and rally drivers. Her fight for equal rights in engineering paved the way for thousands of women. When we get into our car today and look in the rearview mirror, it is worth remembering this extraordinary woman who was not afraid to drive against the flow.